Natural Disasters and Drug Shortages: How Climate Change Is Disrupting Medicines

Dec, 26 2025

Dec, 26 2025

When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, it didn’t just knock out power and destroy homes-it shut down the heart of America’s medicine supply. Nearly one in ten FDA-approved drugs came from that island. Insulin. Sterile IV fluids. Antibiotics. Within weeks, hospitals across the U.S. were rationing. Patients waited. Some died. And it wasn’t an accident. It was a warning.

Why Your Medicine Could Vanish After a Storm

The pharmaceutical industry runs on a fragile system: just-in-time manufacturing, centralized production, and zero backup. When a hurricane, flood, or wildfire hits a single factory, it doesn’t just delay production-it cuts off entire categories of medicine. Take IV fluids. Before Hurricane Helene slammed into North Carolina in September 2024, Baxter’s plant in North Cove was making 1.5 million bags a day. That’s 60% of the U.S. supply. Three days after the storm, hospitals ran out. Elective surgeries were canceled. Cancer patients missed treatments. Emergency rooms switched to saline bags from Europe-after a 28-day approval delay. This isn’t rare. Between 2017 and 2024, climate-related events caused 32% of all drug shortages in the U.S., according to the FDA. And it’s getting worse. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. drug manufacturing facilities sit in counties hit by weather disasters between 2018 and 2023. Hurricanes are the biggest threat, responsible for nearly half of all climate-driven supply breaks. But floods, tornadoes, and even extreme heat are joining the list.Where Your Drugs Are Made-and Why That’s Dangerous

Puerto Rico isn’t the only weak link. Western North Carolina is a hidden epicenter. The town of Marion houses Baxter’s IV fluid plant. Spruce Pine supplies 90% of the ultra-pure quartz used in medical devices like ventilators and dialysis machines. One tornado in Rocky Mount, North Carolina in 2023 knocked out Pfizer’s production of 27 different drugs. A single flood in Michigan in 2022 extended the infant formula crisis by eight weeks because it hit Abbott’s Sturgis facility-already under strain. These aren’t random accidents. They’re structural. The industry has spent decades cutting costs by concentrating production. For sterile injectables-drugs given by IV or injection-78% have only one or two manufacturers in the entire U.S. No backups. No redundancy. One broken power line, one flooded warehouse, one damaged cooling system-and the medicine disappears.How Long Do Shortages Last? The Real Timeline

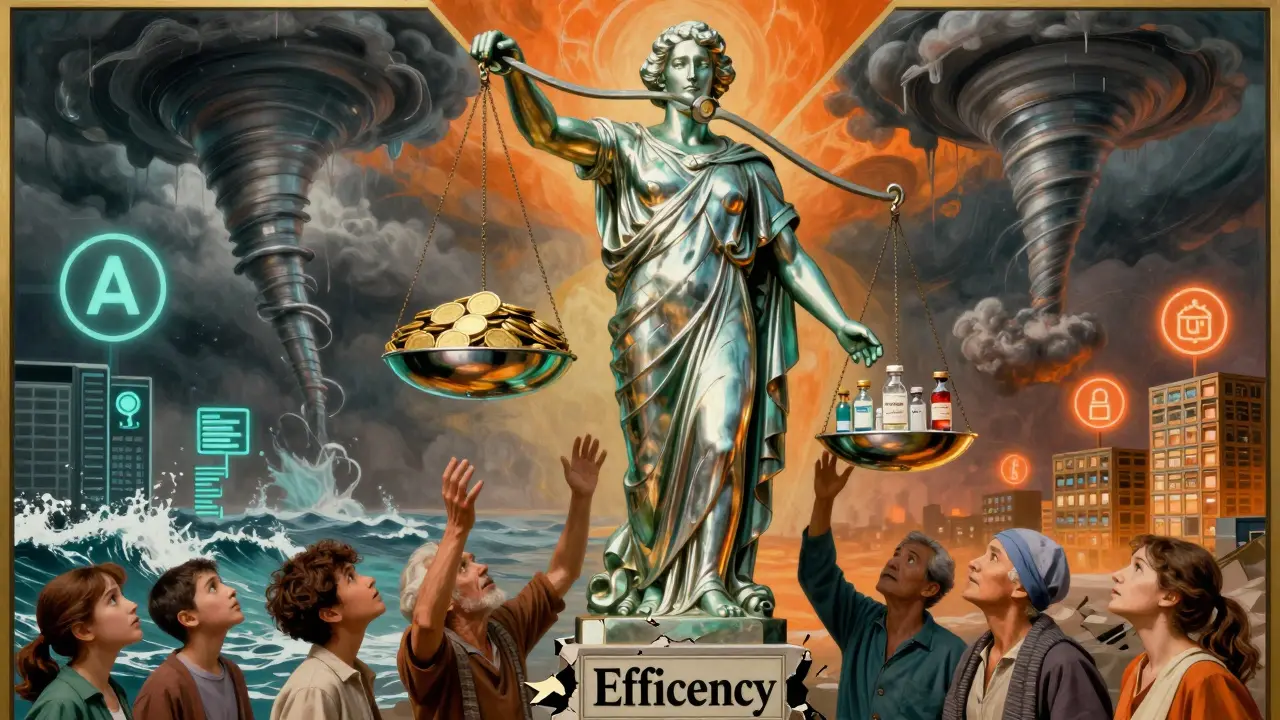

It’s not just about the storm. It’s about what comes after. After Hurricane Maria, it took 11 months to restore power to Puerto Rico’s factories. Insulin shortages lasted 18 months. Why? Because you can’t just flip a switch. Pharmaceutical manufacturing requires precision. Clean rooms. Sterile environments. Specialized equipment that takes two to three years to order and install. New factories? Six to twelve months to build, even under emergency conditions. Compare that to the speed of climate disasters. Hurricane Helene caused an IV fluid shortage within 72 hours. The FDA projected the shortage would last until mid-2025. That’s not a glitch. It’s a design flaw. The system wasn’t built to handle this kind of disruption. It was built for efficiency, not survival.

Who Gets Left Behind?

The impact isn’t equal. Cancer patients, dialysis recipients, newborns, and people with chronic conditions are hit hardest. Generic drugs-like saline, epinephrine, and heparin-are most vulnerable because they’re low-margin. Manufacturers don’t invest in backups for drugs that barely turn a profit. The American Cancer Society found that life-saving cancer drugs have been in chronic shortage for years, and climate disasters make it worse. Smaller hospitals and rural clinics suffer most. Hospitals with 500 or more beds are over three times more likely to have mapped their supply chains and built emergency stockpiles. Smaller ones? They’re flying blind. When IV fluids vanish, they don’t have the staff, the budget, or the connections to find alternatives. Patients in these places are the first to face delays-and the last to get help.What’s Being Done? The Gaps Between Plans and Action

Some progress is happening. The FDA now requires manufacturers to report climate risks. In 2025, new rules will force makers of critical drugs to keep 90-day emergency inventories and submit resilience plans. The Strategic National Stockpile has started piloting regional drug reserves in hurricane zones. AI companies like Sensos.io now predict disasters 14 days ahead, letting hospitals lock in emergency orders. But adoption is slow. Only 31% of top pharmaceutical companies have put real mitigation plans in place. Sixty-eight percent now assess climate risks-but most stop there. Building redundancy costs money. Diversifying production across multiple regions means higher prices. And no one wants to pay more for a drug they’ve always gotten for $2.

The Hard Truth: Resilience Isn’t Free

Some experts argue that forcing drug production back to the U.S. would raise prices by 15-25%. Others say that’s the price of survival. Harvard’s Aaron Kesselheim suggests regionalized global networks with climate-resilient standards. The American Society of Clinical Oncology warns that without action, cancer patients will face treatment delays during 8 to 10 major climate disasters every year by 2027. The math is simple: investing $12-15 billion now in resilient supply chains could cut shortage frequency by 70%. Waiting? It costs lives. And money. A single hospital emergency response to a drug shortage can run over $1 million in overtime, lost procedures, and emergency imports.What You Can Do

You can’t fix the supply chain alone. But you can stay informed. Know which medications you rely on. Ask your pharmacist: Is this drug in short supply? If you’re on insulin, IV therapy, or critical cancer drugs, ask about backup options. Talk to your doctor about alternatives. Keep a 30-day supply on hand if possible. And support policies that demand drugmakers build resilience-not just profit. The next storm is coming. It’s not a question of if. It’s when. And when it hits, your medicine shouldn’t be the first thing to disappear.Why do natural disasters cause drug shortages?

Natural disasters damage or shut down pharmaceutical manufacturing plants, especially in concentrated regions like Puerto Rico and Western North Carolina. These facilities produce critical drugs like IV fluids, insulin, and antibiotics. Because most drugs have only one or two manufacturers in the U.S., a single disaster cuts off supply nationwide. Power outages, flooding, and equipment damage can take months to repair, and new factories take years to build.

Which drugs are most at risk during climate disasters?

Sterile injectables are the most vulnerable-things like saline solution, epinephrine, heparin, and insulin. These drugs are made in just one or two facilities, often in disaster-prone areas. Generic drugs are also at high risk because they’re low-profit, so manufacturers don’t invest in backup systems. Cancer treatments, antibiotics, and infant formula have also been severely impacted during past disasters.

How long do drug shortages last after a hurricane?

Shortages typically last 6 to 18 months after major hurricanes. After Hurricane Maria, insulin shortages lasted 18 months because the power grid took 11 months to fully restore. IV fluid shortages from Hurricane Helene in 2024 are expected to last until mid-2025. The delay isn’t just from physical damage-it’s from the time it takes to get equipment, certify new production lines, and meet regulatory standards.

Are there any solutions being implemented?

Yes. The FDA is requiring manufacturers to keep 90-day emergency stockpiles by 2025. The Strategic National Stockpile is testing regional drug reserves in hurricane zones. Some companies are using AI to predict disasters and adjust supply ahead of time. Hospitals like Mayo Clinic have improved response times by mapping their entire supply chain. But only 31% of major drugmakers have taken meaningful action so far.

Why don’t drug companies make more backups?

Because it’s expensive. Building duplicate facilities, maintaining extra inventory, and diversifying production across regions increases costs by 4-7%. Generic drugs, which make up most of the shortage-prone market, have razor-thin profit margins. Companies choose efficiency over resilience-until a disaster forces their hand. Investors and regulators haven’t demanded change fast enough.

Can I stockpile my own medications?

For some medications, yes-if your doctor approves. Insulin, heart medications, and certain antibiotics can often be safely stored for 30-90 days. But not all drugs can be stockpiled. Some require refrigeration. Others degrade quickly. Always talk to your pharmacist or doctor before keeping extra supplies. They can advise on safe storage and whether your medication is at risk of shortage.

What’s the long-term outlook for drug shortages?

Without major changes, climate-related drug shortages could increase by 150% by 2030. Climate models predict more Category 4 and 5 hurricanes, which directly threaten the 65% of U.S. drug plants in disaster-prone areas. Experts warn that cancer patients could face treatment delays during 8-10 major climate events each year by 2027. The window to act is closing fast.

Gerald Tardif

December 27, 2025 AT 01:50It’s wild how we treat medicine like it’s just another commodity. We optimize for profit margins and call it efficiency-until a storm wipes out a single factory and suddenly people are dying because their insulin vanished. We built a system that works until it doesn’t, and now we’re surprised when the house of cards collapses. We don’t need more reports. We need redundancy. Real, expensive, inconvenient redundancy.

Monika Naumann

December 28, 2025 AT 19:59It is a matter of profound moral failure that a nation so advanced in technology cannot guarantee the basic dignity of life-sustaining pharmaceuticals to its citizens. The West’s obsession with neoliberal efficiency has led to a grotesque fragility in public health infrastructure. One must ask: where is the national will? Where is the collective conscience?

Elizabeth Ganak

December 30, 2025 AT 08:24My grandma’s on dialysis. Last year, they ran out of saline bags for a week and she had to drive 90 minutes to a bigger hospital just to get her treatment. No one talked about it on the news. Just quiet panic. I get that companies don’t want to spend more-but people aren’t numbers. We’re not supposed to be the collateral damage of a cost-cutting spreadsheet.

Nicola George

December 30, 2025 AT 22:48Oh wow. A drug shortage caused by a hurricane? Shocking. Next you’ll tell me water gets wet or fire burns. The real tragedy? We’ve known this was coming for a decade. But instead of preparing, we just kept buying cheaper generics and pretending the system wasn’t one flood away from chaos. Bravo, capitalism. You’re doing great.

Robyn Hays

January 1, 2026 AT 05:11What if we treated medicine like we treat electricity or clean water? We don’t let one power plant be the only source for a city-we have grids, backups, diversification. Why is medicine any different? It’s not just about money. It’s about values. If we believe everyone deserves access to life-saving drugs, then we have to fund the infrastructure to make that real. Not just after the crisis hits.

I’ve been reading about regional drug hubs in the Midwest. Small-scale, climate-resilient production centers. It’s not perfect, but it’s a start. Maybe we stop waiting for a billionaire to fix it and start asking local governments to invest in public health infrastructure like it matters.

Liz Tanner

January 2, 2026 AT 09:54My pharmacist told me last month that my blood thinner might be affected by the next hurricane season. I didn’t know that was even a thing. I’m not a doctor, but I know enough to ask: what’s my backup? What if I can’t get it? This isn’t fearmongering-it’s basic preparedness. Everyone should know what meds are at risk. And if you’re on something critical, talk to your doctor before it’s too late.

Babe Addict

January 3, 2026 AT 07:48Actually, the real issue here is regulatory capture. The FDA’s approval process for new manufacturing lines takes 3-5 years because of bureaucratic over-engineering. If you deregulated sterile production standards and allowed modular, containerized plants to be certified faster, you could rebuild capacity in weeks, not years. It’s not climate-it’s regulation. Also, why are we still using glass IV bags? Aluminum blister packs are lighter, cheaper, and storm-resistant. But no one wants to change the status quo.

Satyakki Bhattacharjee

January 4, 2026 AT 07:11People forget that nature is God’s punishment for greed. We built our temples of medicine on sand, chasing profit like fools. Now the storm comes, and we cry. But the truth is simple: when you forget your duty to others, nature reminds you. No amount of AI or stockpiles can fix a heart that has turned cold.

Kishor Raibole

January 4, 2026 AT 12:26One cannot help but observe, with a mixture of solemnity and existential dread, that the modern pharmaceutical industrial complex has, through a series of calculated optimizations, rendered itself not merely vulnerable-but catastrophically brittle. The very architecture of global supply chains, predicated upon the illusion of perpetual stability, has been exposed as a Faustian bargain: efficiency at the cost of survival. The next hurricane will not be an anomaly; it will be the new normal. And yet, we continue to debate cost-benefit analyses as if the lives of children on dialysis were line items on a balance sheet. This is not merely a policy failure-it is a civilizational dereliction of duty.